This week, the Maplewood Town Committee ordered WhoWeUse to take down our pin drop signs on residents’ lawns. We argued before the Town Committee that the law, which only allowed signs by contractors and real estate brokers for a limited time, was arbitrary and potentially unconstitutional because it violated a person’s right to free speech. When the ordinance was written, the Internet and smartphones did not even exist, nor did digital businesses.

I’ve had some time to research the case law and it turns out I’m not totally off my rocker. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court has actually heard several cases regarding local ordinances restricting the use of signs, and in most cases the Court has found that the ordinances violate a person’s right to free speech.

Ordinances that are not “content-neutral” and restrict certain forms of speech while allowing other forms receive particular scrutiny by the court. The government may place reasonable time, place and manner restrictions on public speech, but these restrictions must be engineered without regard to the content of the speech.

Even content-neutral restrictions can be thrown out if they are overly broad. In Watchtower Bible & Tract Society v Stratton, the Court in 2002 struck down in an 8-1 vote the ordinance of an Ohio town that required all door-to-door advocates of causes, as well as commercial solicitors, to obtain a permit from the mayor’s office. The Court found that the town’s stated interests in protecting residential privacy and preventing fraud were insufficient to justify such a sweeping restriction.

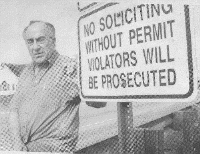

Maplewood also requires the few companies allowed to place signs to get a permit from the town.

In another relatively recent case, City of Ladue v. Margaret P. Gilleo, the Supreme Court ruled in 1994 that a local ordinance restricting the use of signs was unconstitutional.

The city of Ladue had an ordinance prohibiting homeowners from displaying any signs on their property except “residence identification signs, “for sale” signs, and signs warning of safety hazards. The ordinance permitted commercial establishments, churches, and non-profit organizations to erect certain signs that were not allowed at residences.

Ms. Gilleo owned a home in the town and placed a 24- by36-inch sign saying “Say No to War in the Persian Gulf, Call Congress Now.” The sign disappeared. Ms. Gilleo put up another sign but it was knocked to the ground. When she reported the incident to the police, they told her such signs were prohibited. She sued the city, the Mayor and members of the town council alleging the ordinance violated her free speech rights.

The Supreme Court ruled in her favor in 1994. Justice Stevens wrote in a unanimous decision for the court:

Residential signs are an unusually cheap and convenient form of communication. Especially for persons of modest means or limited mobility, a yard or window sign may have no practical substitute. Even for the affluent, the added costs in money or time of taking out a newspaper advertisement, handing out leaflets on the street, or standing in front of one’s house with a hand-held sign may make the difference between participating and not participating in some public debate. Furthermore, a person who puts up a sign at her residence often intends to reach neighbors, an audience that could not be reached nearly as well by other means.

Justice Stevens also shot down concerns of the town that signs would be popping up everywhere, a concern also raised by the Maplewood Mayor.

It bears mentioning that individual residents themselves have strong incentives to keep their own property values up and to prevent “visual clutter” in their own yards and neighborhoods — incentives markedly different from those of persons who erect signs on others’ land, in others’ neighborhoods, or on public property. Residents’ self-interest diminishes the danger of the “unlimited” proliferation of residential signs that concerns the City of Ladue. We are confident that more temperate measures could in large part satisfy Ladue’s stated regulatory needs without harm to the First Amendment rights of its citizens.

One obvious and reasonable solution is to limit the amount of time that all signs can be placed in a person’s property.

Our signs, to be clear, are not advertisements. They are expressions of support by residents in our town of our mobile application and business. But even if they were deemed to be ads, the Supreme Court has also ruled repeatedly that commercial speech is also protected by the first amendment.

So the law is clearly on our side. Now, it’s up to the Maplewood Town Committee to update the ordinance and allow people to speak freely about all types of businesses, especially digital businesses that are growing fast and generating jobs and wealth for communities.

Technology is frequently ahead of the law. But times change. And so should the law.

To support WhoWeUse and all digital businesses, please download our app and like our Facebook page.